Text Riccardo Slavik

‘Style in subculture is, then, pregnant with significance. Its transformations go ‘against nature’, interrupting the process of ‘normalization’. As such, they are gestures, movements towards a speech which offends the ‘silent majority”, which challenges the principle of unity and cohesion, which contradicts the myth of consensus. …It is this alienation from the deceptive ‘innocence’ of appearances which gives the teds, the mods, the punks and no doubt future groups of as yet unimaginable ‘deviants’ the impetus to move from man’s second ‘false nature’ (Barthes, 1972) to a genuinely expressive artifice; a truly subterranean style. ‘ Dick Hebdige: Subculture: The Meaning of Style.

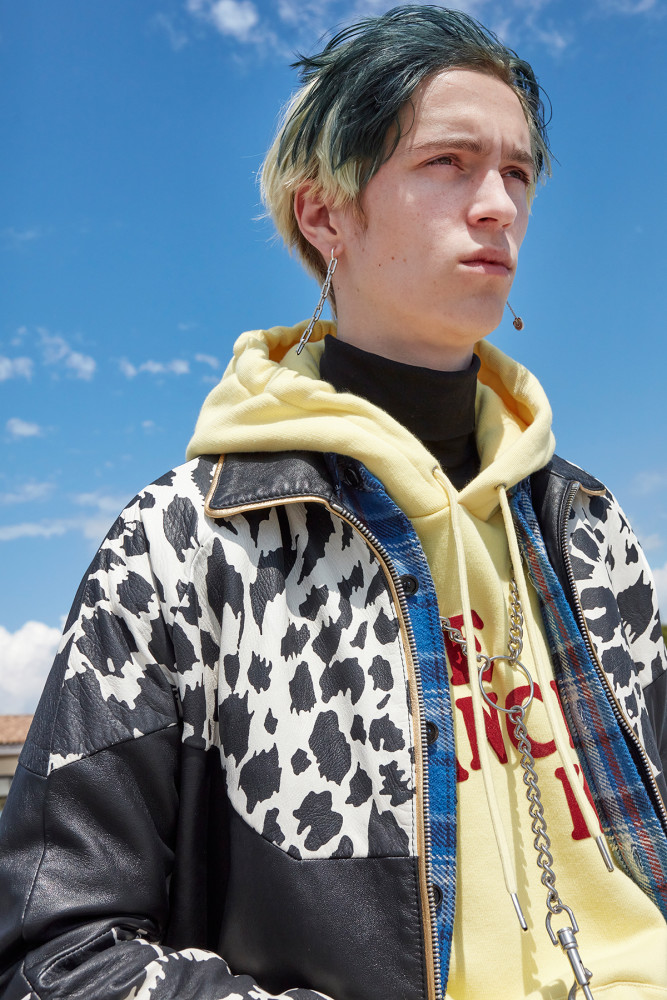

Leave it to Hedi Slimane to emerge from the Covid-19 lockdown with a take on subcultures, Tik Tok, and the latest social media stars, e-boys & e-girls. Titled ‘ The Dancing Kid’, Slimane’s latest collection for the house of Celine is quite a return to form for the creative director, a collection in which he manages to merge his ongoing obsession with youth and style and his knack for creating a ‘believable’ and highly desirable image that takes a mix of vintage research, subcultural history, a swift juggling of tropes and codes, and carelessly and effortlessly throws them together in a perfectly styled and cast package.

Of course e-boys on Tik Tok aren’t a real subculture, generally, the label represents people who have a large presence online ( the e stands for ‘electronic’, obvy) and tote a specific style influenced by skate culture, Emo, Goth, KPOP and Cosplay. But style here is intended as an ‘aesthetic’ or a mix of visual codes, references and color schemes that supposedly make one’s online presence cool, uncool, hot, or not. Style here is totally devoid of any subtext, with the exception of a vague all pervasive irony, which then can only become a droning buzz of fuzzy background noise. To quote Bruce LaBruce :‘When irony became the ideological white noise of the nineties, people were routinely saying the exact opposite of what they meant or authentically believed for ironic effect. But it became problematic when people actually lost track of what they believed in the first place, and they started to take seriously the ironic postures they were adopting.’ Irony is nowadays just part of an aesthetic, a marketing tool, like pastel hair, a cute but sad expression, a meme from an anime. The death of the Subculture has spawned a zombie-culture that propagates through short videos on a Chinese app. The subversive tropes of Punk, Goth, BDSM, are mere accessory to an online presence, just fun, colorful, sprinkles on a hot look, a sheen on a desirable teen object of lust.

Kids today — the new generation — they think in different ways. They don’t even have the knowledge of what a subculture is. It is not relevant to them. If they want to wear a punk shirt, that doesn’t mean that they have to listen to punk music or have a political point of view. They don’t have that mentality. In my generation, when we were grunge, we were grunge. It was a mindset.’ Lotta Volkova in 032c Magazine.

E-boys and e-girls aren’t an actual subculture with rites, music, meeting places, dress codes, one can’t be a ‘poser’ e-boy because being an e-boy AND being a poser are synonymous, the e-boy trope IS the pose, literally, since certain moves and poses are typical of this online tribe. Finally, their online presence is, yes, a teenager’s attempt to comunicate with an outside world, with like minded kids, especially during these times of isolation and distrust, but also, quite practically, a way to gain notoriety, followers, clout, and financial success. These kids aren’t afraid of being cannibalized by the mainstream, they long for it, build towards it.

Such an amorphous yet specific pseudo-subculture is the perfect canvas for Slimane to muse on isolation, self expression in the strict confines of a teenager’s room, and the social repercussions of a pandemic. It also works as a semi-blank slate to take some of these kids’ actual style elements and mold them into a great subcultural mismatch that ultimately plays to the designer’s strengths and personal obsessions. Elements of skater culture, also pervasive in the e-boys’ image, are merged in an apparently haphazard cut and paste way with elements of grunge, punk, 70s vintage, raver culture and even, why not, Disco. Strangely enough the soundtrack to the show isn’t, as usually is the case with Slimane, either interesting or necessary, its droning repetitive rhymes only apparently useful in underscoring an endless loop, a repetition that is, after all, germane to the Tik Tok platform, with its short, serial, dances and videos. The looks however take their influences and run with them in all possible directions and combinations. E-boys, as Rebecca Jennings wrote in a piece for Vox, don’t really exist in real life, theirs is mostly an online presence, they come alive in little dances, funny memes, self deprecating selfies, but their looks aren’t for the outside world, they don’t need to face society with a revolutionary spectacular image.

Even when they do tackle the outside world for vaguely revolutionary or political reasons, it is with irony, and from their rooms. When hundreds, thousands of Tik Tokers and K-Pop fans booked tickets for Trump’s Tulsa rally with no intention of going, effectively tanking the rally and the president’s hopes of a big rally tour, it was a homemade protest, nobody had to go anywhere and actually exist somewhere IRL for it to be extremely effective. The political stunt has had a double effect: exposing the Trump campaign’s weaknesses, thus prompting the president to announce he wants to ban the Chinese -owned app from the US, and giving the world a glimpse of the political potential of this groups of teens that use the app as a way to socialize during the long pandemic lockdown. Still ongoing, the virtual war between the Dotard and Tik Tok users ( now furious over the threat of a ban) has spawned new and interesting tricks, like kids signing up to receive free boxes of Trump campaign material with no intention of ever using them. Inventiveness isn’t lacking in these kids, but what everybody is wondering is: will their rebellion move out of the bedrooms and into the voting booths? Which makes Slimane’s e-boys even more impressive as they strut, at a distance, along an empty race track. They suddenly exist In Real Life, albeit in a luxury fantasy world of premium bleach jeans and vintage looking cashmere kilts. But, and this is ultimately the genius of Slimane’s latest incarnation, they are credible, even though they are more of an abstraction of an idea of a look, that the reflection of an actual cultural trend. And their seeming authenticity is what makes them, and the clothes they wear, desirable, just as their youth, cuteness and ‘irony’ makes the e-boys objets of desire, and, ultimately, quite marketable.